Report 7: The Temple of Artemis at Sardis (2020)

by Fikret Yegül

Chapter 4. Architectural Analysis, Design, and Comparisons

Introduction

The design of the Temple of Artemis at Sardis is unusual because it represents a mixture of different planning approaches applied over a considerable period of time. In many aspects, it is experimental. Unlike many temples, even those that took a long time to complete or were ultimately left unfinished, the Temple of Artemis does not represent a scheme that was conceived at one instance and realized in orderly phases. One could argue in the broadest, most traditional terms that there was an original Hellenistic phase and a Roman Imperial phase, and probably many smaller stages throughout the building process. The first major phase (here referred to as such because it was the first significant, identifiable stage in the building) was complete, in a sense, since the cella must have been ready and functional by the second half of the third century BC. It is exceptional, however, because the original design was finished only as far as the cella, including the in antis columns of the western front and the eastern back porches; none of the exterior mantle of columns, which gives visual substance and style to a Greek temple, was put in place during the Hellenistic phase. No building could ever be conceived without an end design in mind, and in our case we are confident that it would have been a dipteros, much like the early Classical Temple of Artemis at Ephesus and the nearly contemporary Temple of Apollo at Didyma.

It may be hard to imagine that a building so grandly conceived and beautifully executed was only partially realized. It remained looking unfinished and strange, we think, for some four hundred years before construction was taken up again in earnest, only to look even stranger and more unfinished centuries later when finally, by the middle of the fourth century AD, its use as a pagan temple was gradually terminated, transformed in substance and spirit with the addition of a Christian chapel at its southeast corner. However, this is what the facts on the ground indicate. Yet colossal temples, like colossal medieval cathedrals, were rarely finished, or they at least took a very long time to complete. This seemingly unending process of construction was actually a source of pride for the community, who often could not come up with the funds to finish the work. Still, continuing work for all to see was an affirmation of collective faith and determination. A temple finished honored the past; a temple under construction honored past and future.

When the building of our temple resumed during the High Roman Empire as a grand pseudodipteros, it was practically a new temple for a new world, with new needs and expectations. Yet, the centuries separating the original building from the finally realized monument did not entirely erase the intentions of the original builders. The core design of the Hellenistic monument was what shaped and inspired the Roman one. What was obvious to see—in ornament, detail, and style—was admired and even imitated. The memory and the intentions of the original builders were probably never fully lost, and they played a significant, even restricting role in shaping the final design and its execution. Technically speaking, the resulting scheme was an anomaly among the pseudodipteroi of Asia Minor: a creative synthesis of Eastern and Western influences in temple design.

The following is a description of the Hellenistic and Roman phases of the temple as conceived, planned, and executed, and an analysis of its design in the larger context of temple architecture in Asia Minor and the greater Roman world. Much remains unknown and unknowable about many aspects of this design and the construction “phases” of the temple; therefore, some of these will be presented as possibilities, probabilities, and hypotheses. There are strong alternate views, and as before, these alternate views, interpretations of archaeological data, and varying hypotheses regarding reconstruction and dating will be respectfully represented.

Hellenistic Phase Design: The Shape of the Sacred

The placement of the Hellenistic temple might have been conditioned and restricted by two venerable architectural elements on site that predated it: a tufa altar (LA 1) dating to the Lydian period (Plan 2, Plan 6); and a sandstone foundation (“basis”) roughly 58–60 m east of the altar, ca. 6 × 6 m in size, centrally placed at a higher ground level inside the original cella (Fig. 3.5). Butler recognized this platform as an early feature, and this was confirmed by Cahill on architectural, ceramic, and numismatic grounds (see pp. 163-164).1 The present location of the temple, as well as its size and footprint (as either a dipteros or a pseudodipteros), might have been largely guided by the desire to retain these structures; given that the “basis” was placed in the center of the original cella to support the cult image, the present layout represents the largest (i.e., longest) temple that could be achieved around two existing stationary points. As Cahill explained, “Had they moved the temple farther away from the altar, the basis would be been left awkwardly at the front of the cella.”2 The solution brought a certain degree of awkwardness; once the temple’s planned peristyle design was put in place, there would be no room left between altar LA 1 and the front of the cella to place the stairs, which were necessary to negotiate the considerable level difference between the two structures. The western front row of columns (of which only the foundations of the southwest corner column 64 was put in place) was virtually jammed up against the altar; any potential design solution, Hellenistic or Roman, would need to incorporate the altar (LA 1 or LA 2) into the body of the stairs, as Butler attempted in a somewhat fanciful reconstruction (see Fig. 3.1 and pp. 153, note 8). Although such a tight relation might seem awkward, let us be mindful that it was not an uncommon arrangement between temples and their altars during the Greek and Roman periods.3

With its cella measuring 23 × 67.50 m, the Temple of Artemis at Sardis (Fig. 4.1: Hellenistic phase) belongs to the category of very large Ionic dipteroi of Asia Minor, such as the roughly contemporary second Artemision of Ephesus (ca. 334 BC), the Temple of Apollo at Didyma (ca. 300 BC), and the fifth-century BC (“fourth period”) Temple of Hera at Samos (Fig. 4.2); all except the Sardis temple were dipteroi, and continuations of earlier, Archaic predecessors. The cella of the Sardis temple is distinctive not only because of its exceptional size, but also for its unusually elongated proportions. Its length is roughly three times its width, a proportion strikingly similar to the temple group mentioned above (Sardis 1 : 2.94; Didyma 1 : 2.99; Samos 1 : 3.0; Ephesus 1 : 3.10). Such a pronounced elongation of the cella is generally considered an Archaic characteristic. Since the design and proportions of these famous Ionic dipteroi were closely derived from their equally famous Archaic predecessors, the Sardian Artemision could also be linked to those distant-plan prototypes, even though it lacks an earlier predecessor, unlike its Ionian cohort.

The Sardis cella is comparable to those of Samos, Ephesus, and Didyma not only because of its overall proportions but also in its design. The cellas of these temples all display frontal emphasis in their deep pronaoses filled with columns between antae; at Samos there are ten columns in distyle pairs, at Ephesus eight, at Sardis six, and at Didyma an impressive hypostyle of twelve in three tetrastyle rows! Other significant similarities among columnar dimensions and proportions that link the Sardian Artemision to the Ionian examples emerged when the Sardis temple received its peristyle during the Roman Imperial period. The lower diameters of their average column shafts are the same or very close (Sardis 1.99 m and 1.86 m; Didyma 2.01 m; Samos 1.90 m), as are the lower diameter-to-height proportion of their columns (Sardis 1 : 8.91, 1 : 9.61, and 1 : 9.90; Ephesus 1 : 9.6; Didyma 1 : 9.9). Although the column sizes of these three temples are quite close, it is noteworthy that there is considerable difference in their axial spacing. For such a large temple, the Sardian Artemision displays an uncommonly tight, uniform axial spacing along its long sides (taking the columns of the long sides: Sardis 4.99 m; Ephesus 5.73 m; Didyma 5.30 m).

The cella design of the Hellenistic Artemision of Sardis displays a particular affinity to the late Classical Artemision of Ephesus: it follows the same cella arrangement, with a square pronaos and an opisthodomos half as deep as the pronaos. Considering the demonstrable cultural and religious origins of the cult of Artemis at Sardis with that of Ephesus, a corresponding architectural affinity is logical (see pp. 10-11 and pp. 205-6). Merely a generation or so earlier than the Sardis and Didyma temples, we see one of the earliest uses of the opisthodomos in the Ionic order in Pytheos’s Temple of Athena at Priene, finished by 334 BC (Fig. 4.2). This famous temple also boasts a highly ordered, modular application of the same organizational principle of the cella: a square pronaos and an opisthodomos half as deep as the pronaos.4 The immense interior spans of the Temple of Apollo at Didyma and probably also the Ephesian Artemision precluded a roof over their cellas, which resulted in hypaethral adytons (in the former it also served to house the sacred grove of Apollo). At Sardis, however, the use of the double row of internal columns allowed for a more conventional roofed cella. The large numbers of marble roof tiles discovered by the Butler expedition (and many fragments by us) assures us that there was a complete roof over the cella.

An important aspect of the cella interior at Sardis is the exceptionally wide central span between the columns in the north–south direction (restored at ca. 9.30 m on axis with a ca. 6.70 m clear span, a distance that could barely be covered by stone, but there were probably wooden trusses, or doubled beams (or a combination), while the spans of the columns in the lateral (east–west) direction (restored ca. 5.40 m on axis and ca. 2.80–2.90 m clear) would have been suitable for stone architraves (as shown in Fig. 4.14). The distance between the east–west colonnades and the long side walls of the cella (ca. 3.30–3.35 m clear, north–south), although appropriate and normal for stone architraves to span (but which then would have required a triple-mitered joint with the east–west architraves of the colonnades), might simply have been spanned in wood. The exceptional width of the cella nave, convenient for this cella’s later, Roman use as a cult chamber housing colossal images, must have been necessary to accommodate the existing base (“basis”); otherwise, the more closely spaced pronaos colonnade (restored at ca. 8.40 m center to center, 5.82 m clear) and the cella colonnades might have been aligned. In any case, this arrangement emphasized the spatial impact of the nave in a way that is rare in Greek temple architecture. It recalls innovative exceptions, such as the wide cella of the Parthenon in Athens.

Hypothesis for a Dipteros: Archaic and Classical Models

Since the first phase of the Temple of Artemis did not go beyond the elongated cella and the pronaos porch columns in antis, strictly speaking, we do not know what the final design would have been. However, in light of the massive size, the unusual proportions and fine workmanship of the finished cella, and the close similarities with some of the nearly contemporary Ionic temples of Asia (especially the Second Artemision at Ephesus and the Temple of Apollo at Didyma), it takes little imagination to say that the Sardian Artemision must have been planned as a dipteros, the going mode of that time and place. Both of these great and prestigious temples must have still been under construction when ground was broken for the Sardis temple.5 The significance of the favorable political climate following the establishment of Seleucid rule in western Asia Minor has already been underscored, as kings and queens strove to win the approval of their newly conquered subjects by patronizing local cults and temples. Thus, we believe that the original intention at Sardis was to build a dipteros following the general mode and typology of the giant Ionic dipteroi and, like them, harken back to their venerable Archaic predecessors. Simply put, an Archaic-style dipteros was the natural choice for very large, very ambitious temples. Like many of the great Ionian temples, the Sardis temple also must have been intended to be raised on a platform (or given a platform effect by artificially lowering the ground around it) surrounded by steps.6 Perhaps only the earth embankment, and not the defining outer walls or steps of such a platform, was created. The religious, programmatic, and architectural relationship between the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus and the temple at Sardis promises to reward future study.7

Noting the 15.60 m distance left between the ends of the west antae and the altar, one imagines that the west end of the hypothetical dipteros allowed just enough space for three rows of columns while the back east end probably had two rows, again like the contemporary Didymaion and Ephesian examples (in the latter, this distance is exactly 15.70 m). The nature of the original topography remains uncertain, especially the level of the land east of the temple toward the Acropolis, and the changing ground levels between the altar and the cella are critical. This relationship, more or less preserved between the ground on the west front of the temple and the cella interior floor (roughly 4.80 m difference; the difference between the ground and the west pronaos porch is 3.20 m), is therefore a rare physical reference point for the placement of the temple in its natural topographic context. The land must have been rising in a general way from low on the west to high on the east, from the banks of Pactolus to the foothills of the Acropolis, with a somewhat steeper rise at the east end of the temple. However, the steep hill close to the east end (the scarp rises about 15–16 m at a distance of 50–60 m from temple east colonnade) was cut down by Butler in a series of four terraces in order to unearth the temple (Fig. 4.3).8 The entire low-earth terrace upon which the temple naturally sits appears to have been created by successive landslides from the Acropolis heights over time, starting from the pre-occupation period. Geological studies and soil tests undertaken by successive geographers—starting with W. Warfield, geographer of the Princeton Expedition, then G. W. Olson in 1970, and B. Marsh in 2007—all indicate repetitive flooding and silting in the area, and under the present temple by gravel and silt sliding down from the Acropolis.9 Marsh and Olson concluded that the landscape around the temple was largely built by gravel, silt, and clay deposits that washed down from higher ground over time as seasonal rains and changing streambeds mobilized “debris flows” until the temple was entirely buried (mainly by the ninth century AD).10 As pointed out by Cahill, in all deep sondages at or around the temple, “the earliest known stratum is the massive deposit of natural, water-laid gravel and sand under the temple and altar, apparently washed down from the acropolis… [reaching] bedrock 5–6 m below the level of the temple floor, with no intervening cultural horizons… there is nothing… later than the later sixth or earlier fifth BCE [when the sandstone basis was built on top of this gravel].”11

Although the temple never received its peripteral columns during its original phase, its west-facing cella must have been sufficiently complete by the middle of the third century BC to make it a facade for a functioning architectural shrine. The image base was completed, presumably with the image of the Artemis of Sardis installed on it, with a terminus ante quem of ca. 240–220 BC (see pp. 163-164). Rows of columns inside the cella and more between the front and back anta walls must have carried a combination of stone and wood architraves and the wooden trusses of the roof. The roof must have been in place, as it is difficult to conceive of a functioning temple without one, and this is also attested by quantities of handsome marble roof tiles found in both Butler’s and our excavations (see Fig. 1.14). A recently found inscribed roof tile of the temple (Sardis inv. S10.14 = IN10.4) was read by G. Petzl as “φυ(λης) Και(σαρείου?)” and identified as a dedication from Sardian tribes with “Sullan” and “Caesarean” names. Based on this evidence alone it may be suggested that the “name and tribe were adopted in recognition of Tiberius’s support after the earthquake of 17 CE.”12 This is supporting but not absolute evidence for a complete overhaul of the building’s marble tiles and its whole roof, or an argument for two distinct phases—Hellenistic and Julio-Claudian—for the entire building (see pp. 184-189). Rather, it indicates a major repair and overhaul of the damaged original marble roof—perhaps the most vulnerable structural feature of a temple without peripheral columns (modern buildings have their roof tiles repaired or overhauled every twenty to thirty years even without the catastrophe of an earthquake). Indeed it would be reasonable to expect that the earthquake of AD 17 had caused significant damage to the roof tiles. Consequently, during a major roof repair some tiles were newly supplied, others newly “inscribed” on this occasion.

Dedications and Votive Monuments

Large numbers of marble stelae, inscriptions, dedications, religious offerings, statuary, decrees, and public monuments dating from the Lydian-Persian period to the third century AD have been found inside and around the temple, or in the sanctuary before the establishment of the temple. The majority, however, belong to the period of the temple. Among the roughly one hundred public, honorific, and votive inscriptions found and published by the Butler expedition, some twenty-six come from the temple or are associated with it.13

From an eye-catching monument of the Imperial era incorporating Archaic lions and eagles on a statue base of ca. 550–520 BC dedicated to Artemis in Greek and Lydian by one Nannas14 to long lists of individual families whose names are recorded as trusted keepers or administrators of the temple through the third and second centuries BC;15 from high officials and leading citizens of Sardis, like Menogenes, whose generosity and services to his homeland during the reign of Augustus were publicly named and acknowledged, to one Polybius, an aspiring Greek rhetor of the second century AD, who was moved to honor Cicero, his distant muse in Rome, by erecting a bust of the great Latin orator in the precinct;16 from a royal dedication to Artemis by the Attalid king Eumenes of Pergamon (probably Eumenes II, ca. 190 BC), to another great ruler who was honored some 350 years later, the emperor Antoninus Pius, “on account of his benevolence” to the city;17 from a curious stone ball dedicated ca. 300 BC to the goddess by a very young noble girl who would be queen, to many curious balls with similar dedications to Artemis by generations of girls who were her priestesses through the second and first centuries BC;18 from dedications honoring the priestesses of Artemis on marble blocks or slabs which might have been structural19 to one special block that supported the statue of one priestess who gave voice to her timeless plea: “O, Artemis, ever preserve Sardis in concord by the prayers of Moschine, the daughter of Diphilos!”20—the sanctuary and Temple of Artemis, from the Hellenistic era into the empire, were the focus of Sardians’ devotions and prayers, and the depository of their gifts. Although firmly anchored as the center of the cult of goddess Artemis, the city’s heterogeneous cultural past and its multilayered sense of religious syncretism gave a deeper, more tolerant sense of sanctity to the land subsumed under the goddess’s broad and inclusive spiritual mantle. That this center of devotion and possibly political and economic power extended into the middle of the second century AD and included the worship of Roman emperors and empresses—and that Artemis’s old temple now received their divine images (with enthusiasm or willy-nilly)—is simply the historical confirmation that royal Sardis, city of the Panhellenion and twice neokoros, upheld its proud place among the constellation of Asian cities subsumed by the empire.

Honor and devotion to the goddess continued unabated through the centuries. Still, the physical presence on the ground, the architectural focus of all that devotion, was less than perfect. If we were to encounter the Sanctuary of Artemis at Sardis in the late Hellenistic or early Imperial era, we could be excused for being startled by the bizarre and uncommon appearance of Artemis’s temple: an oddly proportioned, long, tall marble box with shining white walls accented by discrete, exquisite details, covered by a simple roof of marble tiles with gabled ends—rather like a toy house magically transformed into a magnificent marble palace. This white marble box rose on a gentle earth embankment—its hard-edged form in contrast with the natural, lovely roll of the hilly countryside around and the spiky mountains behind—in repose between the banks of the Pactolus and the craggy Acropolis peak that linked the city to the legendary range of the Tmolos Mountains beyond. Beyond the valley of the Pactolus, the land opened toward the north to the wide Hermus plain with its “thousand mounds” of the Lydian kings and nobles, and the famed golden city of Croesus. Around the box of the temple, softening its stark geometry, there must have been trees and bushes and many small votive monuments, inscriptions, stelae, and statues. Sardians must have known and appreciated that their temple was incomplete without its external columns, although, in the words of a reviewer of this manuscript they might have been “less bothered by the absence of outer columns than an Ionian city would have been. The long hall [with nineteen-meter-high walls] would have provided them with an impressive setting for Artemis.”21 To the followers of the goddess this slightly bizarre and unusual shape set among the hills must have become, over time, acceptable and cherished—indeed, the shape of the sacred. In that sense, there was nothing unusual, nothing bizarre.

The West End and the Northwest Stairs

Today it is easy to be baffled by the clutter of structures occupying the area from LA 1/LA 2 to the west pronaos porch, whose physical, functional, and chronological relationships with each other are confusing and even contradictory (Plan 3). The main question is the nature of the physical connection between the temple and the Archaic and Hellenistic altars (LA 1 and LA 2, respectively) during different periods in their histories and how they relate to the northwest stairs that extend between the northwest anta pier and altar LA 2, some 1.20–1.30 m beyond the outer face of the west peristyle. We will summarize what we know of the original topography of the temple’s west end and the primary level changes and other alterations brought about by Butler’s excavations.22 In the following discussion of the west end I mainly follow N. Cahill’s archaeological interpretation and overall reconstruction, with a few alternative ideas.23 I present this discussion through the Hellenistic and Roman periods in order to retain a more unified picture of this area over time.

The temple cella was built over the course of the third century BC atop a relatively low platform of earth that surrounded the cella, so the relationship between the early altar and the temple’s west end must have been a natural one; the nonexistent peristyle of columns was probably evoked by the gentle slope of the earth platform surrounding the cella, made either by building the ground up, digging it down, or both. The drop in the land to the north and south of the temple, which today looks like a trough, was created by Butler’s deep trenching and does not represent the original topography, which we simply do not know. What is certain is that there should have been some form of a natural pteroma (a sort of earthen walkway whose width at the same level of the euthynteria—i.e., at *100.0—we do not know) along the sides, because the deep foundations of these walls had to be buried. Located on the west end was the Archaic altar (LA 1, ca. 550–500 BC), which almost doubled in size with the Hellenistic era altar (LA 2), approached by wide steps on the west side. By the time work on LA 2 began (ca. 280 BC, coeval with the temple or a little earlier; we have no secure date for it), the ground level in front of it its west-facing steps was at ca. *96.80, ca. 1.40–1.50 m lower than its top, preserved at ca.*98.30.

Thus, the original ground level in front of LA 1/LA 2 was some 3.20 m lower than the platform upon which the temple was built, i.e., the pronaos and pteroma set at *100.0. This high level was probably in response to the natural rise of the land toward the east. The level of the cella proper was still another 1.60–1.70 m higher than its pronaos (ca. *101.70), making it nearly 4.80–4.90 m higher than the original ground in front of the altar (Plan 3). This unusually large difference in level between the cella interior and the natural ground in front of the altar may have been partially dictated by the pre-temple “basis” located inside the Hellenistic cella (or subsumed by the cella)—as well as other architectural and topographical factors that are poorly understood today—and a desire to present the temple in a higher position, at a topographical advantage to its immediate surroundings. Although the total leveling of the temple platform or pteroma at *100.0, for a rise of ca. 3.20–3.30 m over a length of ca. 85 m, was mild if not negligible (roughly resulting in a ca. 4 percent slope) as one approached the temple from the west, this level difference had to be negotiated by stairs and/or ramps. Furthermore, this height difference would have to be negotiated within the restricted space between the back of altar LA 2 and the west face of the new temple along its northwest and southwest antae, a distance of ca. 16.60 m.

The obvious solution would have been to build a broad, monumental flight of stairs across the entire west front of the cella porch, rising the full 3.20 m from the base level of the altar at * 96.80 to the west pronaos porch at *100.0 (Fig. 4.4, proposal 1). This would have been a massive construction with about fourteen risers (risers at ca. 23 cm and treads at ca. 36–36.5 cm) and extending out beyond the temple’s west face some 4.70–4.80 m. The north pteroma, however rudimentary and berm-like, was at *100.0 (since the foundations of the wall would have to be properly buried in the ground at the very least), making the connection between the north pteroma and the west end of the temple, with this 3.20 m level difference, difficult and awkward, especially where they meet at the northwest and possibly the southwest corners. A straight north–south wall (essentially a retaining wall) or a steep berm to demarcate the west end of the north pteroma could be thought of as the obvious and cleanest solution. On the face of it, this arrangement presents two problems: first, the sheer monumentality and abruptness of the stairs in such a confined, low space, would be visually jarring; second, at the northwest corner of the anta (where the north and west faces of the anta pier meet) the foundations of the anta and of the north wall would have been exposed, with blocks hanging some 1.60–1.70 m over the level of the earth. This could have been revetted neatly in marble, but that is not a structural solution. More importantly, such an arrangement lacks precedent in Greek and Hellenistic temple architecture. Frontal schemes in Roman podium temples are common enough, but that phase of our temple was not Roman.24 Yet the unorthodox design, elsewhere argued as the reason for other creative aspects of our temple, may well provide the answer for this unusual but impressive arrangement.

An alternative proposal would be to divide the difference in height in half by partially filling and raising the space between the altar and the temple to a height of about 1.50–1.60 m, or roughly to that of the altar top at ca. *98.30; in essence, this would create some sort of a higher open space like a plaza between them. The advantage of this solution would be to reduce the height of the west front stairs and the wall terminating the west end of the north pteroma to a more manageable 1.70 m (leading up from ca. *98.30 to *100.0).25 A hypothetical reconstruction drawing provides a visual aid for such an arrangement but does not confirm it (Fig. 4.4, proposal 2).

The problem with this proposal is the presence of a stele (number 15, assigned by Butler), apparently in situ, at the lower *96.80 level, against the roughly plastered wall of the altar (Figs. 4.5, 4.6).26 Thus, in order to propose an alternative arrangement for a higher ground level here, one has to assume that stele 15 was not in its original position but was moved there by Butler or by Roman builders of the temple’s west front. Or, alternatively, that LA 2 (whose exact date we do not know) was somewhat earlier than the temple, and its west face was plastered and the stele put in front of this wall before the temple was built, then buried; this is possible but not supported by evidence.27

During the Roman phase, the pseudodipteral plan was adopted and the original west wall of the cella was moved forward, toward the west, to create the double cella; work also started on the six-column pronaos porch of the west end, reflected in the design of the better-preserved prostyle porch of the east end (Fig. 4.1, Roman phases). The area between LA 2 and the west porch—which today is deeply cut up by Butler’s trenches—was filled to erect the porch columns (columns 48, 53, 54, 55, and 49) and the extensive mortared-rubble construction that encased them. A large portion of the debris in the west porch area, the rubble retaining walls between the altar and the pronaos porch, and some of the mortared-rubble construction between columns 54 and 55 were all removed by Butler.

It must be emphasized that in our opinion this major Roman phase was a part of an integrated “running design phase” for the entire temple without specific “early” or “late” Roman phases with hard dates. It was a construction process that must have taken a long time and moved from east to west as a succession of stages. It is in this sense that we see the west end—between the altar and the Hellenistic era steps leading up to the pronaos and then to the cella—as an area where Roman construction might have started almost concurrently with the east end. The north and south pteromas and their peristyle colonnades must have just been begun on the east side but were not yet extended to the west. Since the area between the altar and the extended, columnar pronaos porch was too narrow for a stair that could negotiate the full level difference, a new staircase on the north side of the porch was created on new mortared-rubble foundations (probably using the blocks of the Hellenistic era stairs discussed above).28 This is what we call the “northwest stairs” (Figs. 2.129, 2.154, 4.5). The area must have been filled with earth to the level of the porch floor (ca. *100.0) that was defined and partially retained by rubble walls ca. 2 m high and extending north and south of LA 2. These walls were largely removed by Butler, though they can be seen on his “actual state plan.”29 The east end of the northwest stairs was delimited by a “crude wall” of small blocks and mortared-rubble construction extending north, connecting the northwest anta pier to column foundation 45. It supported the fill of the north pteroma, which must have been in the process of being built in stages from east to west (Fig. 4.7). As Cahill notes, the north peristyle foundations eventually continued to the west end of the temple, and “the [northwest] stairs must have been considered a temporary arrangement.”30

The northwest stairs extend for a length of ca. 16.60 m between the “crude wall” on the east (with a 1.10 m space between the crude wall, which makes an almost ninety degree, 1.20 meter–thick dogleg against the north cella wall and the end of the steps) and the mortared-rubble wall on the northeast corner of LA 2 on the west (Fig. 2.129). The stair on its eastern end is preserved in five courses; on the west, only the bottom two courses remain. They can be reconstructed in seven risers that negotiate the total height of ca. 1.70 m, from the bottom at ca. *98.30 to the west pronaos floor at *100.0. The steps are constructed in white marble blocks varying in lengths of 0.45–2.20 m, and these display excellent workmanship with delicate, “raised” vertical joints. Their fine workmanship and small bar clamps (13–16 cm long, some misaligned and none functional) suggest Hellenistic or early Roman work, but it is clear that they were used here as spolia, reset and refitted, possibly from their original use as the Hellenistic era stairs leading up to the west pronaos porch.31 The stairs are supported (or backed) by mortared-rubble construction similar to what surrounds the foundations of the peripheral columns. On the eastern end of the steps, between the northwest anta pier and column 48 before it, the marble foundations are preserved at two courses below the paving level and show extensive pedestrian use; the entire western portion, in front of missing columns 52 and 59, plunges down some 1.60–1.70 m to the lower ground level at ca. *97.0, which extends as a kind of “deep corridor” between the exposed foundations of the columns of the pronaos porch (columns 53–55) and the great altar. The deep corridor as we see it today is simply a trench excavated by Butler; this is misleading in appearance, as is the “plunge” behind the stairs, which would not have existed when the stairs were operational (Figs. 4.5, 4.6).32

The mortared-rubble “crude wall” was excavated in 2010 and found to be bonded into the stairs at its south end; apparently it served as a retaining wall to support the east end of the north pteroma (Figs. 4.7, 4.8, 4.9). Although preserved in rough-rubble construction, it probably had a more presentable stone or marble veneer on its west face.33 The northern end of the rubble wall was cut by the mortared-rubble encasing of the north pteroma column foundations, mainly that of column 45; the west face of its south end is visible ca. 1.80 m from the east end of the stair. As observed by Cahill, “The peristyle must therefore postdate the wall and stairs, and these features were never used together; when stairs were in use, the peristyle foundations had not been laid here; when they were laid, the space between the peristyle and stairs must have been filled, burying the wall and the stairs.”34

The northwest stairs and the platform created between the west pronaos and the altar was the primary means of access to the west front of the temple during its early Roman phase, before the north peristyle columns had been extended this far west. Another means of access to the west pronaos area seems to have been provided from the south by stone stairs at the southwest end of the temple (a parallel arrangement), now preserved poorly in two steps. The northwest stairs could have been installed at almost any time before the construction of the peristyle column foundations of the west end (numbers 45, 47, and 51, the foundations for column 57 never laid; see Fig. 2.129). The construction of the west-end columns of the north peristyle, which buried the stairs, also could have been undertaken at almost any time between the mid-second century AD and the abandonment of the temple in the late fourth century. Yet, since the northwest stairs should logically be associated with the building of the six-column west pronaos porch, we believe that when work on the north pteroma and its columns (or column foundations) had sufficiently advanced by the later second century, the makeshift arrangement of the northwest stairs became unnecessary and unsupportable. Our explanation for the heavily eroded blocks two courses below the surface between the northwest anta and column 48 is less satisfactory (see Fig. 2.107); perhaps the stairs were dug up in late antiquity, when most of the fine marble blocks of the temple, including those of the stairs, had been robbed and this crude, functional passage merely 2.20 m wide served those who had business among the ruins.

-

Şek. Plan 2

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. Plan 6

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 3.5

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 3.1

()

-

Şek. 4.1

()

-

Şek. 4.2

()

-

Şek. 4.14

()

-

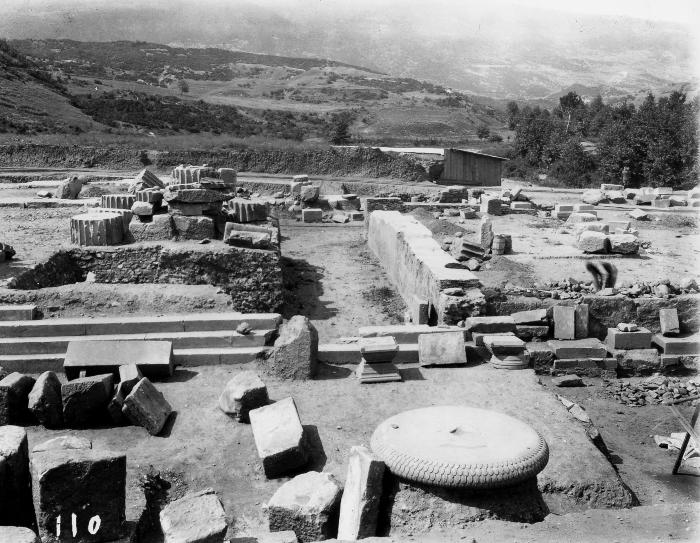

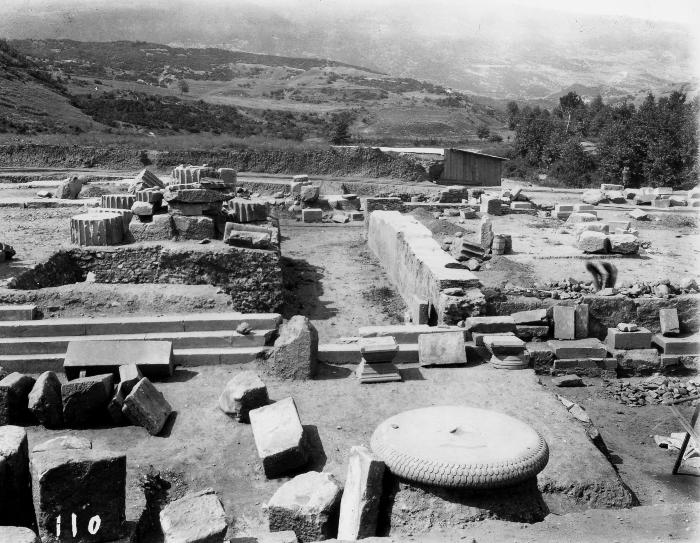

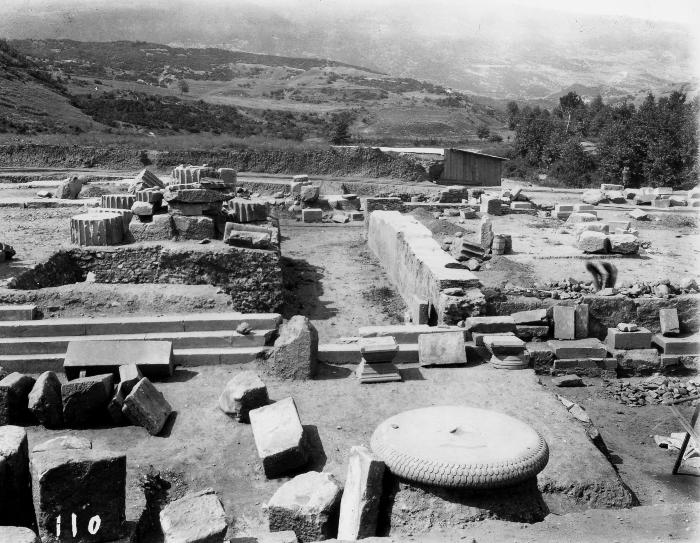

Şek. 4.3

(Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 1.14

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. Plan 3

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 4.4

()

-

Şek. 4.5

(Howard Crosby Butler Arşiv, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 4.6

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 2.129

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 2.154

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 4.7

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 4.8

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 4.9

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 2.107

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

Roman Phase Design: The Shape of Power

The Roman construction of the temple commenced sometime in the Hadrianic era following a loosely conceived, pseudodipteral model with eight columns at the ends and twenty along the sides. Since the impetus for the “new” temple appears to have been to incorporate the imperial cult, the manner in which this was done, obviously, was to divide the cella into two nearly equal parts: the east accommodated the cult statues of the imperial family and faced the Acropolis; the west (further extended some 10.15 m westward), as in the original arrangement, belonged to Artemis. It is a strong possibility that there was an imperial cult altar on the east side, balancing the great altar of Artemis on the west side but far smaller in size, set against the towering east front columns, or possibly set inside the spacious pronaos porch in front of the stairs of the east door; since no remains of such a structure was found, one has to assume that it had shallow foundations and was totally destroyed and demolished during the Early Christian era. With a planned mantle of sixty-four columns, the full project was gigantic and ambitious, arguably the largest “pseudodipteral” temple in the world, and it progressed over centuries. Its peripteros of columns was still largely unfinished when the temple lost its pagan meaning and purpose in the fourth century AD.

At first glance, it is difficult to imagine that the great temple of the Sardian Artemis existed and served as a cella only for some four hundred years, all the way into the Roman Imperial era. Perhaps that is one of the reasons that theories for a major Hellenistic era rebuilding (Gruben’s and Hanfmann’s “second phase”), even in scholarly publication, are attractive and will not go away.35 Furthermore, the desire to explain the present “pseudodipteral” plan of the temple as a development directly influenced and inspired by Hermogenes’s exceptionally successful and timely innovation—hence the desire to connect the Sardis temple with Hermogenes—has been too seductive to resist in some of the published histories of the temple. How could one of the most imposing and renowned pseudodipteral temples of all time not have a connection to Hermogenes, whose magnum opus lies some eighty kilometers southwest of Sardis as the crow flies? Or, uncharitably, to credit the Romans as the creators of this remarkable architectural program and beautiful columns and capitals is too unsettling to accept. Chronologies for the temple’s alleged “late Hellenistic phase” differ from 220–200 BC (Hanfmann) to 190–150 BC (Gruben); anything resembling general agreement among scholars on the chronology of the Anatolian architect’s productive years (i.e., 225–175 BC, or possibly even later, ca. 175–125 BC) is a fairly recent phenomenon.36 Yet, as I have tried to show in this study—through technical and construction manner; archaeological evidence; stylistic, architectural, and functional analyses; historical indicators; inscriptions that speak; and reasonable circumstantial deductions based on the meaning and intent—the evidence precludes the interpretation of the pseudodipteral arrangement at Sardis as anything but Roman Imperial, a scheme causally linked to the double-cella plan created for the imperial cult occasioned by the city’s second neokorate. Our best estimate for this event, which signals the “second major phase” of the temple, is Hadrianic (ca. AD 130–60). As mentioned earlier, there is no cogent or compelling evidence for a major intermediary Hellenistic or early Roman phase, unless we conceive of “phases” as a succession of many construction processes in the Roman period and adopt a somewhat minimalist definition of what constitutes a phase in the history of a building. An important event that is tempting to associate with major rebuilding, primarily the design and partial erection of the peripteral columns, was the earthquake of AD 17 which devastated Asia Minor and according to sources, caused the worst damage at Sardis. The disaster was partly but generously alleviated by cash grants and tax remissions under Tiberius (Tacitus, Ann. 2.47). However, we have no idea how much damage this earthquake caused in the temple except for, surely, its marble roof.37 However, if the earthquake had inflicted serious or even minor damage upon the existing temple, the first order of business, in my opinion, would have been to repair this damage, not to start a ruinously expensive new building phase. Periodic and sundry repairs, routine maintenance work, renovations, and even schemes that were started and soon abandoned must have been normal for a monument with a history that spanned many centuries. Such reparation and renovation work often leaves little or no evidence—or the evidence is too elusive and confusing to follow cogently—and may be indicated as hypothetical possibilities rather than substantive phases in the building history of the temple. When the second-century Roman building commenced to surround the Hellenistic cella with a peristyle, it roughly followed the pseudodipteral arrangement we have, creating a gargantuan building out of an already very large one, its footprint some 2.7 times larger than its Hellenistic predecessor (Fig. 4.10).

Perhaps the exceptionally long time span between the completion of the Hellenistic cella and its commencement toward a proper peripteros is not as surprising as it first appears. For its users, a finished cella housing the sacred image was all that would have mattered in defining the sacred bond between the goddess and her worshippers. As underlined by F. Rumscheid, any classically inspired cella with the cult image inside was a “cult building.”38 The peripteral columns adding conventional grandeur could and would come later. Indeed, by delaying their construction—after having spent so much money for so long on the exquisite marble cella—the community could gain some financial respite and divert its funds to other worthy civic projects, such as a theater, a bouleuterion, or a basilica. O. Bingöl extended this logic to Magnesia—also basing his observations on technical and stylistic considerations of peristyle elements of the Hermogenes’s Temple of Artemis there—and made the bold proposition that even this temple might not have advanced beyond the cella stage during the master’s lifetime, but received its external colonnades sometime in the late first century BC or even later—now made more plausible with the discovery of a donor inscription for these columns datable to the early Imperial period. In this scenario, Vitruvius’s elaborate description of this iconic temple’s proportional system must have been based not on built-site observations, but rather on Hermogenes’s descriptive treatise.39

Complex Interaxial Contractions and the Importance of the New East Front

Introduced during the Roman rebuilding phase of the temple is a special convention of Archaic Ionic design known as multiple or complex interaxial contractions, present in the frontal row of columns where the axial spacing between them (or their columnar axes) regularly increases, starting from the ends toward the center. The eastern front of eight columns employs four different spatial variations (subtlety noted and admired by the Neoclassical architect C. R. Cockerell). Each interaxial pair flanking the center decreases in width from 7.06 m (the widest at the center) to 6.64 m, 5.45 m, and 5.31 m at the ends; the interaxial spacing of the long sides keep a uniform, narrow spacing of 4.99 m.40 The locus classicus of this system is at both the Archaic and subsequent Late Classical Artemisia of Ephesus where, according to recent investigations by A. Ohnesorg, the Archaic (“Croesus”) and Late Classical temples shared identical plans and had multiple interaxial contractions with four gradations on their western fronts.41 The evidence for this is not absolute, but it is convincing and suggests that the Temple of Artemis of Ephesus in its distant Archaic version, but more readily in its Late Classical, provided the model for the sophisticated interaxial contractions of the east peristyle columns of the Sardis temple in Roman times. Since only one of the column foundations (number 64) of the west peristyle had been laid, one cannot know if the Roman builders intended to apply multiple interaxial contractions on the west peristyle as well, though it is probably unlikely. At the Heraion in Samos, interaxial spacing is graded down from 8.40 m in the center, to the next pair on either side at 7.04 m, and the outer pair at the ends at 6.55 m (Figs. 4.1, 4.2). The back of this temple (with nine columns) did not employ this system. The Hellenistic Temple of Apollo at Didyma with ten columns in front and back retains uniform spacing all around; it is impossible to know for sure if its Archaic predecessor (completely covered by the later temple) used this system, but neither reconstruction alternative, by Gruben and more recently by B. Fehr, indicates it (Fig. 4.2).42 Thus this particular feature represented in various forms in the Archaic (and possibly Classical) temples at Ephesus and Samos, and so consummately applied at Sardis, represents a deliberate Roman revival of a patently Archaic model. It is also interesting to consider that the Roman temple builders of Sardis ignored the simpler model of equal spacing front and back that had been applied at the Hellenistic Didymaion in favor of more distant historical models.

It is also interesting that this sophisticated, archaizing system was applied only when the east end of the temple (the opisthodomos of the original cella) had become a new front during the Roman rebuilding. We cannot be sure of if such multiple contractions could have been a consideration for the Hellenistic temple; simply, there are no exterior columns and therefore no evidence. However, if columns had been built, it might have been applied only to the west, which was the proper front of the temple. Among the Archaic and (possibly) Classical examples known to us, this system is always used only on the principal facade of a temple. It is surely an indication of the extraordinary importance of the new east front, created solely for its mid-second century association with the imperial cult, that it received an extraordinary design with its full eight columns and carefully applied, historically conscious, catenated interaxial contractions (and perhaps planned, even if not executed, with a magnificent pediment)—while at the west end, the goddess still awaited a facade. Would the system of complex contractions have been applied also on the west facade if it had been built? Another intriguing and important point: Why did the once-principal west facade leading to the goddess’s chamber remain incomplete, or at best, was a truncated-looking tetrastyle porch? Despite arguments for the apparent topographical complications involved in achieving a full west facade, and of course the problems of cost that the political realities of second-century Sardis might have dictated (perhaps after a fight in the city council?), the architectural precedence enjoyed by the imperial gods was at the expense of the old goddess. This is not to say that every significant public dedication in Roman Sardis (such as the Marble Court of the Bath-Gymnasium Complex) did not start evoking the goddess’s name; but then one might say, as epigraphic formulas go, that talk is cheap. It also furnishes us with one of our stronger arguments for a second-century date for the construction of the east end of the temple rather than a Julio-Claudian date; only the Hadrianic (and later Antonine) admission of the imperial cult into the temple could have supplied the rationale for making the east end a new, primary front. If prestige and primacy were not conferred upon the east side by the admission of the imperial cult in the east cella in the second century, the Roman builders would have had no reason to turn this end into the primary facade.

The Divided Cella and the Exterior Columns

We imagine that by the mid-second century AD, the original west-facing cella of the temple was divided by the east crosswall into two chambers of nearly equal length (west cella interior length is 26.74 m, east cella interior is 25.16 m). In order to create sufficient space for the two cellas, the west wall of the original cella was dismantled and rebuilt ca. 10.10–10.13 m toward the west, thus incorporating roughly two-thirds of the original pronaos (Fig. 4.11). The west crosswall (the new western front wall of the temple) extended between the north and south walls of the pronaos porch, not bonding to them, and obliterated porch columns 79 and 80 (Figs. 2.65, 2.67). As discussed above, this operation also involved moving and rebuilding the cella door and stairs in the new location. Since the pronaos floor was ca. 1.60–1.70 m lower than the cella, the floor of the new addition to the western chamber had to be filled to the level of the original cella and a new roof and support structure devised. These operations, especially relating and adjusting the existing gabled roof of the Hellenistic cella to the much wider roof of a temple with peristyle, probably required dismantling and rebuilding the whole roof, even though much of this peristyle had never progressed beyond foundation stage. The new east and west pronaos porches of the two-cella temple were now equal in depth at 6.0 m, i.e., the depth of the original, east-facing opisthodomos. A monumental door with finely ornamented jambs and lintel was cut into the east wall, the original blank back wall of the temple (Fig. 2.181). Approached by a flight of steps, this door gave access to the new east chamber, which we believe was reserved to house the colossal imperial images and honored the imperial cult (Fig. 3.64). A similar door and stairs must have been made for the new west wall (or moved from their position on the original west wall), but nothing of these elements survived.

Following these operations within the cella (or concurrent with them), there must have been a massive attempt to realize the pseudodipteral scheme by laying out some of the foundations of the peristyle columns. Fifteen, but possibly as many as eighteen columns of the east end, including the eight frontal columns, were completed while only the columns of the pronaos porch of the west end were complete. The foundations and the plinths of five of the six columns of the west pronaos porch have been preserved to varying degrees, leaving the northwest corner column, number 52, missing; it was either never started or completely robbed. All others display smooth, finished tops with construction lines and markings that provide evidence for the columns they carried. Particularly, foundation blocks of columns 53 and 54 provide critical information that these columns had pedestal bases comparable to those of columns 11 and 12; the square plinth of column 53, in situ, shows clear markings of a square upper member, not circular as one would normally expect for the spira (round bottom element) of a regular Asiatic-Ionic base (Fig. 2.157). Corroborating evidence is also provided by C. F. Stanfield’s 1830s watercolor showing a few columns standing in the distant background; these could only be the columns of the west porch (Fig. 1.27). Furthermore, no less than fourteen or fifteen fallen fluted column drums inside and around the west porch were found mainly at the west end and the majority grouped together by Butler between the column foundations 53 and 54.

The appearance of the north and south long sides of the temple must have been uneven and visually disconcerting as well. Of the twenty column positions of the north side, only two (numbers 9 and 15) must have had bases and columns. On the south colonnade only column foundation 18 (third from the southeast corner) is fully preserved; the foundations on either side of number 18 (numbers 14 and 20) probably had columns (Fig. 2.199).43 Of the fifty-two peristyle column positions, only ten or eleven (or, eight or ten) had never been started, even in foundations, which is itself a major undertaking. Almost all of the north and south colonnades were in place, to some degree at least, intended to be completed sometime. Still, by the time the pagan temple was abandoned over the course of the fourth century, only a few foundations had actual column bases, and fewer had columns on them.

We do not know if the construction of the bases progressed concurrently or piecemeal—probably the latter, with several at one time. To erect even one of those massive columns was a laborious and costly task that could have relied on the generosity of a patron or a group of patrons. It is interesting, however, that the epigraphic message of column 4 names no particular donor (nor “public funds”), but rather the temple’s own resources as the source of this exceptional column, possibly the quarries owned by the temple. The erection of the temple columns must have progressed slowly and sporadically as funds allowed. Still, it is curious that none of the finished columns of the temple name a donor; after all, each of these columns must have been conceived as a milestone in the completion of the temple in financial, visual, and symbolic terms. Perhaps the very visible and massive act of constructing a row of columns 18 meters tall, a monumental civic achievement, trumped the naming of donors. It is also true that different cities of ancient Anatolia had different traditions or levels of generosity in public giving; while a city like Aphrodisias or Magnesia presents an unusually rich record of public munificence and donors’ names, Sardis has far fewer.44 However, it is more likely that the temple, a venerable civic and economic entity, owned the Mağara Deresi quarries (or portions of them since they are extensive) and paid for its columns over a period of time. Yet, after the politically significant and well planned east-end columns that heralded the imperial cult chamber were in place (and recorded in a laudatory manner by a “talking column”), and the erection of the six-column west pronaos porch, the minimal architectural gesture of monumental entry for Artemis’s own chamber was achieved, and whatever the reason, enthusiasm for further column erections appears to have waned.

A Pre-Modern Ruin?

The appearance of the unfinished temple, despite nearly two centuries of work since the commencement of the Roman phase, must have been intriguing—at least from some angles, visually awkward. How could the mighty Romans rule Sardis during its wealthiest period in Asia Minor, one might ask, yet allow such an important project to remain unfinished? Some colleagues, such as R. R. R. Smith, have asked—ostensibly seriously and certainly creatively—if Sardis left its “new old temple consciously unfinished.” The question posed is more intellectual than shocking. Was this, indeed, an intentional and sophisticated desire to experience the building as an artistic “ruin”? While we may disagree with the concept of an outright intentional ruin (especially in the ancient world), it may be worth going beyond the heterodoxy of this view and rethink the question in a broader context, in which the explanation “they never got around to finish it” is not good enough.45 The lure and pleasure of ruins, a popular theme in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Romanticism of Giovanni Battista Piranesi and Hubert Robert, among others, was mockingly revisited in the Postmodernism of 1970s. In a sense, the imagining of a building’s ruins, or imagining a building as a part of a “ruined composition,” is the opposite of its construction/reconstruction cycle, giving license to a greater play of imagination; it is an exercise in restitution. John Pinto quoted Piranesi, a master restitutor of ancient buildings as imaginative ruins, as remarking, “Speaking ruins have filled my spirit with images that accurate drawings would have never succeeded in conveying.” Piranesi might as well have said, with equal cogency, that an incomplete ancient temple could fill one’s spirit with images in a way that a finished one could never do.46

The motivation behind the visually engaging or simply outrageous modern ruin—such as the set of Best Company stores (especially the showroom at Sacramento, 1977, with its iconic “notched” facade, Fig. 4.12)—founded on whimsical aesthetic and social commentary, was at least partially serious. Although our own explanation for our unfinished temple is mainly based on economy and opportunity (rather than artistic delight in sublunary things), and therefore a lot more practical (and dull), we admire the boldness of such an idea in its capacity to challenge the conventional limits of perception, inspire new horizons of thinking, and start new debates on the nature and meaning of classical art and architecture. Some of our proposals about the temple are impossible to verify on hard evidence, so we, too, rely on just that kind of thinking and reasoning. Some of these concerns and questions have been taken up with penetrating wit by R. Harbison, whose chapter on “ruins” in The Built, the Unbuilt, and the Unbuildable starts: “Ruins are ideal: the perceiver’s attitudes count so heavily that one is tempted to say ruins are a way of seeing.” And in reference to the “bizarre design” of Best stores, Harbison observes, “who would have thought that contemporary American shoppers could entertain simultaneously the consumer’s fiction of… shiny function and fantasies of decay?” As delightfully imagined, if the great Artemision of Sardis was designed as or allowed to be an artistic, premodern ruin, what fiction of function or fantasy of decay could the Sardians entertain?47

The Imperial Outlook: An Unfinished Temple

A late second-century AD view of the temple from the east would have been quite impressive and calculatedly deceptive (Figs. 4.10, 4.13). Eight magnificent columns of the east facade, with their tall, unfluted, powerful shafts and possibly a massive pediment, rose against the broad mass of the mountain behind the necropolis hill to the west. An altar dedicated to the imperial cult would be expected here, though none was found. Although no actual remains of the frieze or the cornice have been found, a hypothetical restoration could consist of a cornice decorated with modillions and dentils and a plain frieze like the Pantheon’s—a familiar combination in imperial architecture. The temple must have been raised on a simple embankment or platform like a berm, already proposed for the Hellenistic cella, then regularized and extended out as a proper pteroma, probably not even paved. A crepidoma of six or eight steps built on a mortared-rubble backing, like the ones preserved for the comparable Ionic temples at Ephesus or Didyma—or the early Imperial Wadi B temple at Sardis—must have been intended but was either not constructed or only constructed at a few locations for limited lengths.48 The platform of mortared-rubble construction of the pteroma intermittently and variably projected beyond the line of the peripteral columns. It is on the basis of these possibilities that “idealized,” hypothetical reconstructions of the temple, both inside and outside, have been attempted on paper (Figs. 4.13, 4.14).

In reality, the apparent and quasi-finished grandeur of the east front was an illusion. Along the north and south sides there were only a few isolated columns, the great majority of their places empty with either just a few bases, unfinished bases, only huge foundation blocks, or possibly, in a few locations, nothing at all. The great pediment and the full-width, gabled roof it fronted, if attempted, awkwardly narrowed down and faded out against the narrower cella roof; this might have happened logically along the north–south alignment of columns 21 and 22, with the east wall of the cella in between them. Pteromas must have existed but were not yet roofed, except, as projected, at the east end of the temple. If one viewed the Roman temple from an unfavorable angle, the outlook would have been even more edgy and abstruse than its Hellenistic single-cella predecessor. In contrast to the fully built east front, the west front had a much smaller pediment, or simply an architrave, that was supported by the four front columns of the pronaos porch, resembling a simple prostyle temple writ large—very large. Colleagues have asked, but it is difficult to say how the roof over this mixed shape was configured; the connection between the elongated gabled roof covering just the cella and the wider, full roof of the east end, which partially covered the unfinished pteromas, would have been awkward—although there are a few acceptable ways that this could be achieved with relative visual and structural grace. I present one technical and aesthetic possibility in my reconstruction drawings (Figs. 4.13, 4.14). The most likely hypothesis is a full pediment that covers the east porch at a higher roofline, then continues over the cella with a break (possibly across the line of the cella east wall, as mentioned before) and a separate, simple gabled roof at a slightly lower level.49 The application (really, grafting) of a larger, wider, but slightly lower Roman era pediment upon the narrow facade of the Hellenistic temple of Demeter at Pergamon demonstrates the solution for a similar problem (Fig. 4.15).50 Furthermore, one should remember that any sense of the visual and structural abstruseness attributed to the unfinished temple as a building is, to a certain extent, a reflection of our own cultural and visual perceptions and prejudices; a believer of the ancient world would have seen something deeper in the sacred nature of the shrine and its impressive and moving geography than its apparent static, physical shell—perhaps, something that merges the magnificence of appearance with the ethics of purpose.51

A recent digital reconstruction of the pictorial qualities and visual effects of the Temple of Artemis at Magnesia by L. Haselberger and S. Holzman analyzes the exceptional qualities of pseudodipteral temples with rich contrasts of light and shade, associating this experience to the notion of asperitas (propter asperitatem intercolumniorum), which Vi-truvius uses in his admiring description of the architectural qualities of Hermogenes’s novel, pseudodipteral arrangement (De architectura 3.3.9).52 The Latin word and the notion it expresses are imprecise and flexible, quite different from more familiar literary implications of “asperity.” As Haselberger and Holzman argue, Vitruvius might have alluded to rich, scenographic effects and the “illusion of relief” created by the well-lit row of columns set against the dark depth of the hall-like pteromas that are typical of pseudodipteral temples. Digital restorations of light and shadow simulations of the west facade of Hermogenes’s Temple of Artemis at Magnesia as a pseudodipteros (which it is), along with comparisons to simulations as a dipteros or a peripteros, recreate varieties of spatial depth and quality, or grandeur and dignity (Fig. 4.16). While this notion (as well as the modern-day drafting styles it engenders) lacks precision, we have always emphasized the spatial qualities of the Sardis pseudodipteros in architectonic and scenographic terms, though without recourse to the Vitruvian asperitas.53 Indeed it is the particular strength (and “magnificence”) of our temple, with its immense, hall-like ambulatories where spatial and scenographic effects would have doubled in intensity and certainly in grandeur, as compared to the experience of Hermogenes’s temple in Magnesia (Fig. 4.16).54 Furthermore, at the east and west ends where the ambulatories wrapped around the cella and merged into porches that (probably) soared to light, the contrasting and changing effects of light and dark would have been stunning (Fig. 4.17). From a distance, the sense of architectural “illusion and grandeur” of this largest of all pseudodipteral temples—whether the Vitruvian asperitas or not—must have been enhanced by the natural grandeur of the craggy Acropolis and the rolling Tmolos Mountains.

The interiors of the double cellas must have afforded a more traditional appearance. On the west, preceded by a simple but monumental and possibly unfinished pronaos porch, the old goddess of the Sardians reigned in her new, spacious cella; and judging by the number of votive monuments of Roman date, she continued to enjoy the love and respect she was accustomed to under the new regime. What she might have lacked in terms of a proper temple frontage, she must have made up by the prestige of her venerable altar, which we believe was integrated into the west porch across an elevated “plaza” as in the old days, or the spacious enclosure of the six-column pronaos porch. On the opposite side facing east (Fig. 4.13), the new imperial gods and goddesses enjoyed all the advantages and privileges of politically expedient newcomers inside their traditionally arranged, columnar cella (Figs. 3.63, 3.64). Lords and masters in matters practical, and acknowledged as such in the archaistic and erudite but sometimes bombastic language of Asia’s learned philosophers of the Second Sophistic, their cult and iconic presence were heralded by a suitably impressive temple facade, a shape that served as an effective reminder of the power and circumstance of the new Roman Sardis, even if the facade and what it represented (to some) was an illusion.

If we look at the bigger picture, the apparently untidy impression caused by the centuries-long Roman building and rebuilding of an “always unfinished” edifice, becomes a phenomenon with some positive civic and religious connotations. The roughly textured, unfinished surfaces contrasting against and alternating with the finely finished and polished moldings and joints would have conveyed the image of a powerful, even willful sense of rustication and enhanced the readability of the temple as an integrated whole of variegated marble masses and planes. Furthermore, such a bold and mannered display of architecture in various stages of finish—always “in progress”—could have invoked an underlying sense of appreciation for the skill and effort imbued in the process of construction, hence a sense of inherent monumentality orchestrated to the scale of time. As observed by D. Favro in reference to the frenzied state of construction of Rome under Augustus and other emperors, so, too, the Sardian Artemision—from the slopes of the Acropolis to the valley of the Pactolus—must have looked and sounded like a massive jobsite: networks of scaffolding and cranes; piles of building materials; the constant din of moving, heaving, and lifting; the rhythmic rattle and clatter of carving, shaping, chipping, and scraping—and marble everywhere—all a perennial show of labor and progress to bolster the drama of civic achievement in the service of the city and its gods, celestial and imperial.55 Every step in the process marked the passage of time, measurable in detail but immeasurable and eternal in wholeness. Every impeccably carved detail, every perfectly rounded molding teased out of roughly shaped stone by master masons, reflected the community’s homage to its deities and became the visible, tangible proof of it.

Such a chaotic state of construction was a common scene in Rome and in Roman cities, especially in second-century Asia Minor, and a symbol of messy vitality. The signifier of progress is process, which the leaders of Roman Sardis must have been keen to sustain, although there is little evidence for major construction at the temple beyond the late Antonine era, except perhaps the addition of a foundation or two for the columns of the long peristyle. A finished project was indeed cause for pride and celebration (and repose of arrival); but the perpetual state of construction of an exceptional building, polishing and finishing, must have been cause for perpetual celebration in joining the past to the present.

-

Şek. 4.10

()

-

Şek. 4.1

()

-

Şek. 4.2

()

-

Şek. 4.11

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 2.65

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 2.67

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 2.181

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 3.64

()

-

Şek. 2.157

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 1.27

()

-

Şek. 2.199

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 4.12

(Telif hakkı Sart Amerikan Hafriyat Heyeti / Harvard Üniversitesi)

-

Şek. 4.13

()

-

Şek. 4.14

()

-

Şek. 4.15

()

-

Şek. 4.16

()

-

Şek. 4.17

()

-

Şek. 3.63

()

Architectural Analysis and Comparisons

The application of the pseudodipteral plan at Sardis occurred not as a natural development in the wake of Hermogenes’s new and prestigious temple in Magnesia, nor its many prestigious followers in Asia Minor, but rather as a deliberate and historicizing choice centuries after the master’s architectural landmark and its canonization by Vitruvius (3.2.6; 3.3). In Magnesia, Hermogenes created (or planned) an ambulatory of two uniform, interaxial widths all around the cella; all columns are equally spaced, with the exception of the wider-spaced pair in the middle (Fig. 4.20). At Sardis, not only does spacing between the columns vary progressively following an Archaic convention, but also the ambulatories at the ends of the temple are wider than the sides (three-intercolumniation ends versus two-intercolumniation sides). As pointed out by Howe, the Roman era pseudodipteros at Sardis is not a pseudodipteros at all, technically speaking.56 Furthermore, by creating spacious, projecting six-column pronaos porches within the columnar enclosure of the temple’s ends, and pushing them forward into the normal intercolumnar space against the frontal rows (in effect, occupying this pseudodipteral corridor), the Sardis temple violates the basic rule behind pseudodipteral design—or, in terms of scenographic and visual drama, improves upon it.

The Creation of Space

A normal pseudodipteral arrangement (and one in line with other Roman era pseudodipteroi in Asia Minor, such as the temples at Ankara and Aezane; Figs. 3.75, 3.76) would have favored a simple tetrastyle-prostyle internal porch enveloped by a continuous, uniform double-intercolumniation-wide ambulatory. This “logical” and canonical solution, for which there were clear and available models, was obviously never the case for Sardis, where unusual, triple-intercolumniation-deep pronaos porches enclose and capture space like magnificent halls in a way that a straight-front tetrastyle or hexastyle porch arrangement does not and cannot.57 These large, immensely tall, “cubical halls” defined by the six columns of the porch and the projecting arms of the anta walls might have even been open to the sky (Fig. 4.17). Even if we accept that the original columns in antis were retained into the Hadrianic phase for simple structural expedience, and that this space was covered by a high, timber-trussed roof (which might have contained a more modest sky opening) by carving a void in the heart of the pronaos—as opposed to the forest of even-spaced columns that occupy the same areas in the contemporary Artemision of Ephesus or the Temple of Apollo at Didyma—the Sardian Artemision would have still projected a bold and expanding sense of space, exploited through its unorthodox plan. Space and visual drama, the play of light and shadow and of material and void induced by the great, soaring hole framed by tall, slender Ionic columns of the “pseudo-pseudodipteros”—the “dazzling effect” of propter asperitatem intercolumniorum—would have been overpowering. Consider first the ambulatories that are 9 m wide and 92 m long, defined on one side by the smooth, sheer, stark, unornamented nineteen-meter rise of a marble wall, and on the other a tightly spaced, overlapping rhythm of monumental columns of the same height (Fig. 4.18)—a lofty, hard-edged corridor of rhythmic lights and shadows terminated at each end by single, tall, anthropomorphic, iconic columns merged into the expanding volume of a pronaos, rising to about nineteen meters like a tower of light shot through a mass slashed by shadows. This was an experience of surface and space not commonly found in the orderly, canonical temple architecture of Hermogenes and his followers.58 In its monumental impact and “dazzling effect,” it went beyond anything that a Hermogenean pseudodipteros could create. I believe the sources and inspirations were hybrid, and although they were anchored at home and in its predecessor, they also lay further afield.

Mixed Sources and Traditions behind the Sardis Artemision

In assessing the nature of Roman architecture in Asia Minor over fifty years ago, J. B. Ward-Perkins identified two broad currents: buildings that followed local, Hellenistic traditions and those that took Italy and the West for inspiration due to a lack of suitable models at home. He found that religious architecture belonged “decisively to the former category.”59 Undoubtedly there is truth and simplification in this view. Such binary positions, more fashionable in the 1970s than now, have both strengths and limitations. While searching for cultural sources behind traditions is a valid form of analysis, one should be prepared to accept that the end product is often more than the sum of its parts. This is especially true in Asia Minor, where a rich patrimony of cultural resources and vigorous borrowings blur the hybrid origins of architecture, as well as its unusual and unique results. This is the background against which we should view the Temple of Artemis at Sardis, whose design does not represent the simple following of an idea or a recognizable type, but lots of ideas and types shaped by fortuitous circumstances and deliberate choices—a situation true not only for this one temple, but for Roman architecture in Anatolia in general.60 There is precedence but also serendipity here—the desire to follow tradition, to re-create memory, but also novelty and the deliberate rejection of memory. We have already emphasized the role of the great Ionian temples in shaping the cella of the first phase of the Sardian temple (Fig. 4.2; see in this chapter pp. 229-231). One must remember the daunting choice faced by the Roman architect(s) who inherited this long, narrow, austere, archaizing cella squeezed tight between a venerable altar at one end and the rising ground hugging the steep Acropolis at the other; the challenge to fashion a mantle of columns around a naked cella that must have been as formidable as it was unique (Figs. 4.1, 4.10). The resulting design, starting from an honored, extant structure and reshaping it into an idiosyncratic variant of a broadly conceived pseudodipteros, benefited from sources rooted in local as well as foreign traditions. The Roman re-creation of the Artemis Temple at Sardis is as remarkable as it is problematic because it has little to do with the familiar and regular Hermogenean tradition of pseudodipteros type that was established in Asia Minor by the middle or end of the second century BC.

The question lingers as to who was responsible for the exceptional design of Artemis’s temple at Sardis through its historical trajectory from Hermogenes to Hadrian. Who inherited history and reshaped it into a creative variant of a “broadly conceived pseudodipteros?” A vibrant, wealthy, busily building regional center like Sardis must have had many architects and master builders at work during the Imperial period. Yet given the paucity of information on the names and careers of ancient architects, especially for those working outside Rome, the task of finding who is daunting, achieved more through luck than design. Compared to the many questions we are confronted with regarding this great temple, the lack of information about its architect(s) is the one causing the least worry. Still, we may be visited by such luck in a very modest, tentative way.

An Architect from the Vine-Rich Tmolos